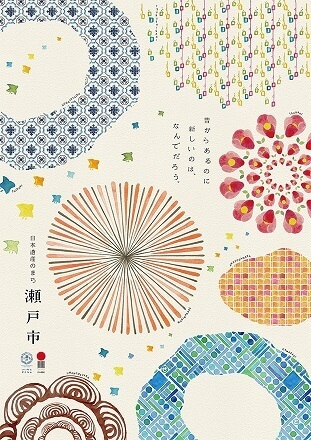

Seto City, Aichi

Origins of “Setomono” (translates to “pottery” in Japanese), one of the world's leading production areas

Seto is one of the world's most renowned and rare production areas, which has continuously been producing pottery for almost 1000 years. In Japan, the word "setomono" refers to “pottery”. The term originates from Seto ware, which has been at the forefront of pottery-making throughout Japan's long history of pottery making. The origins of Seto ware come from the Sanage kilns, which were producing sue ware in the latter half of the fifth century in the area which is now know as the Higashiyama Hills of Nagoya. In this hilly area, there was a stratum called the Seto Group, from which it was possible to collect raw materials for pottery, such as high quality kibushi and gairome clay, as well as quartz sand, which is a raw material for glass. The Seto area was abundant in natural resources, such as pine trees, which played an active role in the development of the ceramic industry in the area. At the end of the 12th century, the production of Koseto pottery started. At the time it was the only area in the country known for domestic glazed pottery production, and included the production of items such as shijiko “four ear” pots, bottles, and vessel for replenishing ink stones. In the 19th century, production of porcelain began and exchange with the foreign countries flourished exporting to the United States and exhibiting at international fairs. Due to this, Japan also adopted Western techniques such as the use of cobalt oxide, a pigment used for dyeing, and mold forming methods using plaster. Seto continue to produce a wide variety of products such as tableware, novelty items, porcelain teeth, and car parts, catering to the ever-changing lifestyles of the times.

Visit Constituent Cultural Property

Ash-glazed bottle with rope-shaped handle

Ash-glazed bottle with rope-shaped handle