Tambasasayama City, Hyogo

Pottery production interwoven with everyday lifestyle

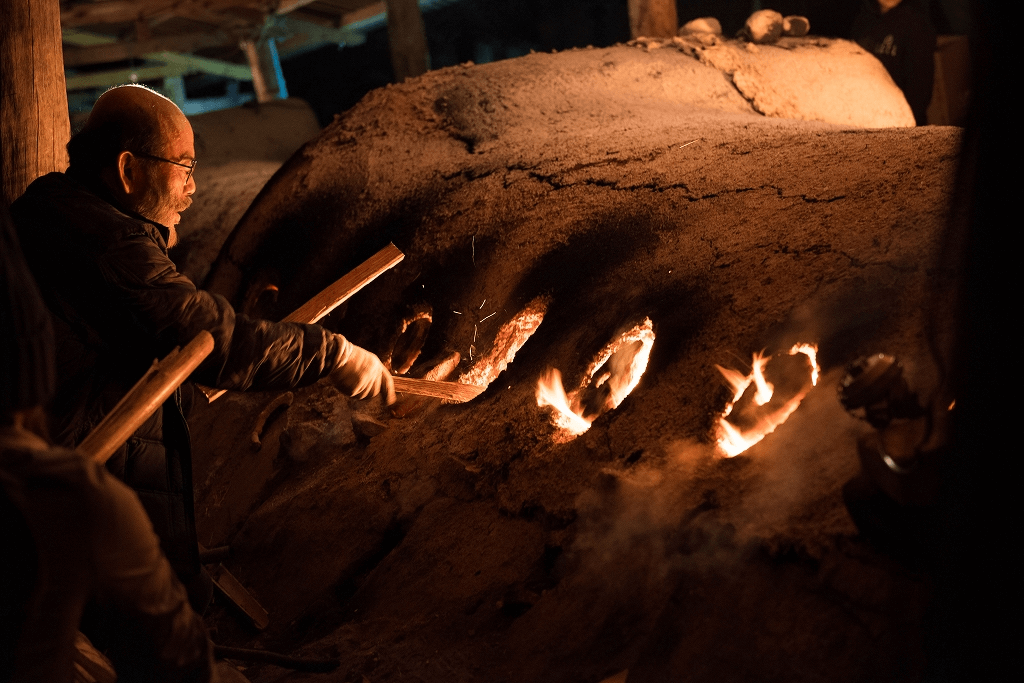

Tambasasayama is located in close proximity to Kyoto and Osaka, sandwiched between mountains Kokuzosan and Wadenjiyama, along with the Shitodanigawa River. The main kilns were lined up in an area where the fog, which was particular to the Tamba region, would clear up quickly, making it a suitable place for drying pottery. The origin of Tamba ware dates back to the late Heian period(Heian period:794-1185) to the early Kamakura period(Kamakura period:1185-1333). During these times, there was a high demand for everyday items such as pots, urns, and mortars, and anagama (cellar kilns), which were dug into hillsides and covered with roofs, were used to produce such items. At the end of Keicho period(Keicho period:1596-1615), the Korean noborigama (climbing kiln) was introduced, making it possible for a larger number of products to be fired in a short amount of firing time. With new techniques and inventions such as “kerokuro” (a wheel operated by kicking) and "yuyaku"(glazes) made from ash and iron, potters actively began to create household items. In the late Edo period(Edo period:1603-1867), the quality of products improved with the introduction of new glazes and clay. The combining of different types of glazes also created new finishes and patterns, and many new products were produced.

In the Showa 20's(1945-1955), new products such as "kisha-chabin" (tea canteens mainly used in train carriages) and blocks were created. In the Showa 40's (1965-1975), on the other hand, the folk craft output in this region skyrocketed due to encouragement from pottery instructors and folk craft movement activists. Tamba ware is still relevant in today's society, producing daily items while maintaining its tradition.

Visit Constituent Cultural Property

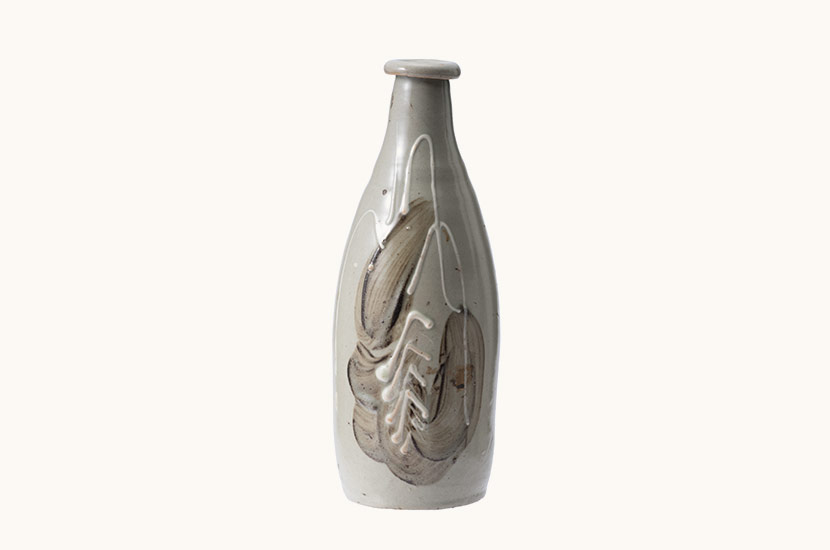

Bowl

Bowl